Renée Modot

I didn’t mind sitting for the portraits or some nudes, but you should have seen my living room when he was finished for the day.

— Renée Modot

April 23, 2024

Hiding in Plain Sight: Renée Modot

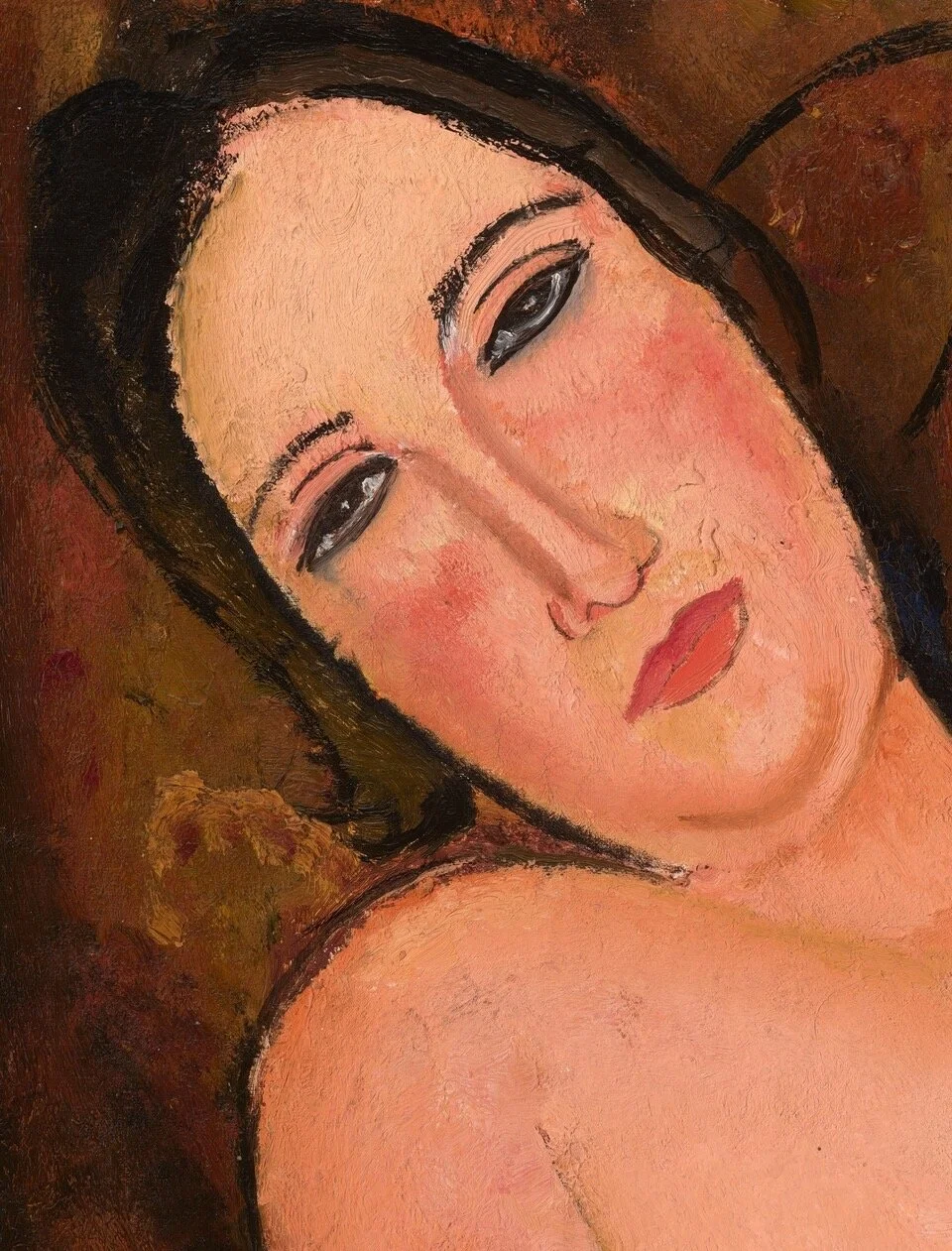

The model is the wife of a French moving picture actor. She is known as “Mado”[sic].

This annotation appears on the original inventory record for Nude on a Divan, a painting dated 1918 in the Chester Dale Collection at the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.(fig. 1). A further note specifies that the work was painted in Nice.[1] Despite these intriguing clues, until now the alluring model in the painting has never been positively identified. New archival research reveals that she was Renée Modot (1894–1978), wife of the French film actor Gaston Modot (1887–1970)(fig. 2).

(fig. 1)

Nude on a Divan, 1918. National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. Chester Dale Collection

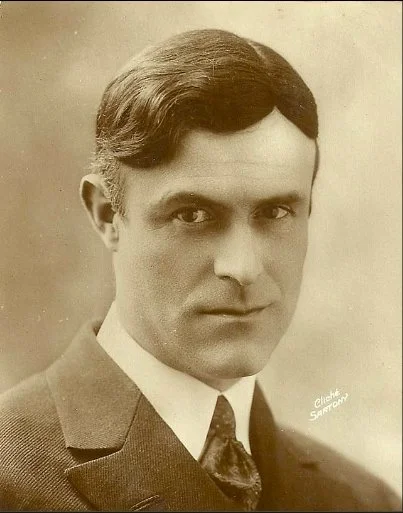

Modigliani first befriended Gaston Modot during his early years in Montmartre, while both were working as artists. The two briefly shared an abandoned shack at the top of the Butte of Montmartre, which they referred to as “La Maison du Curé.”[2] Modot, endowed with good looks and an athletic physique, would soon shift careers and, by 1913, he was making a name for himself as a leading actor in silent films, equally adept at playing a daredevil as he was at portraying the quintessential villain.

(fig. 2)

Gaston Modot, postcard by Editions Cinémagazine, no. 416.

Photo: Cliché Sartony

.

Gaston and Renée (née Montalant) likely became a couple by early 1918.[3] Around this time, Renée later recalled, she first met Modigliani in Paris and described him as a “handsome and likeable man and most pleasant.”[4] They met again in Nice in the summer of 1918, where they were all living at the time. Persuaded by his dealer, Léopold Zborowski, Modigliani and his companion, Jeanne Hébuterne, had left Paris for the south of France in early April of that year, escaping the heavy German bombardments of the capital, and hoping to find an antidote to the artist’s worsening health.

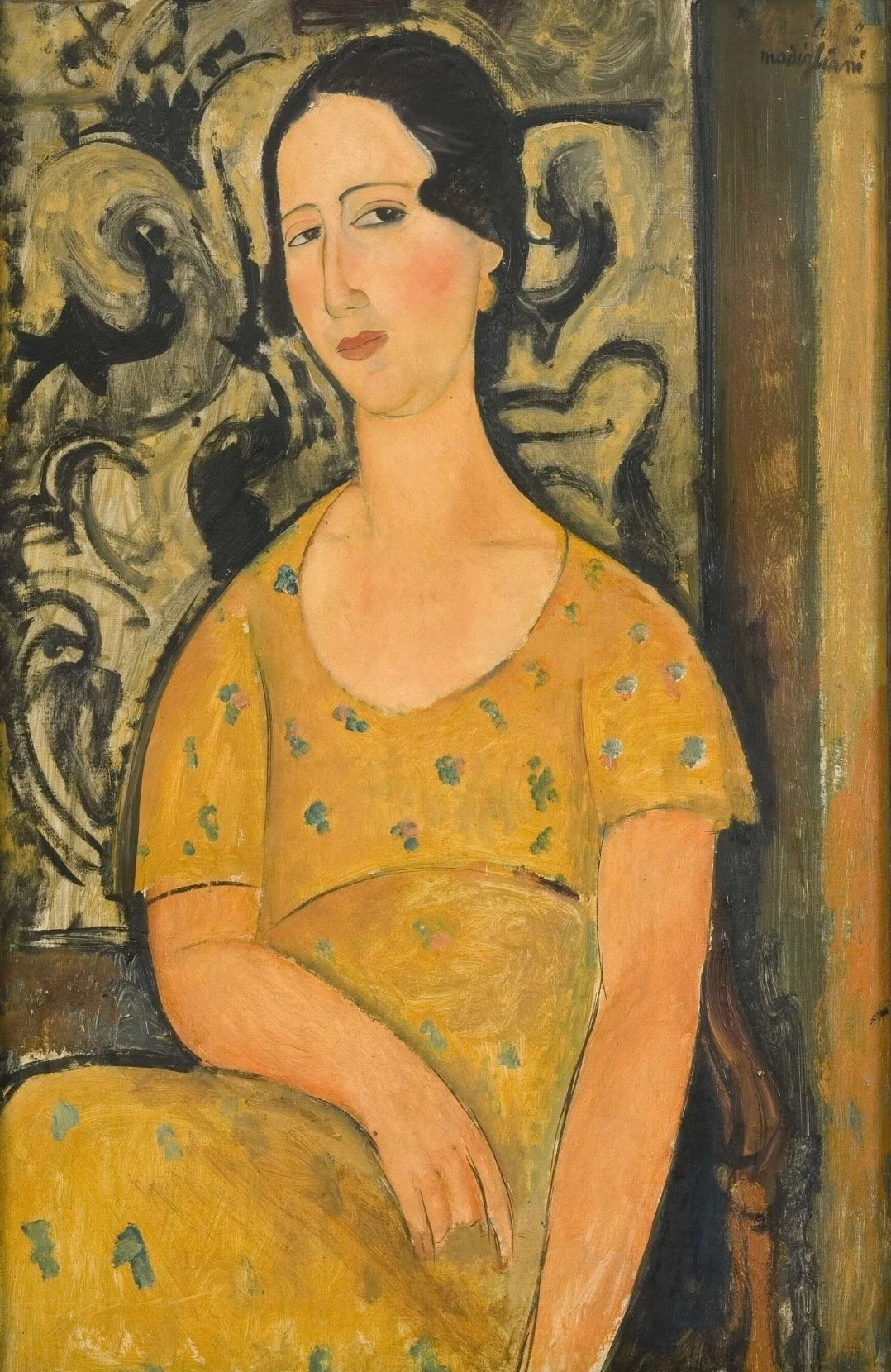

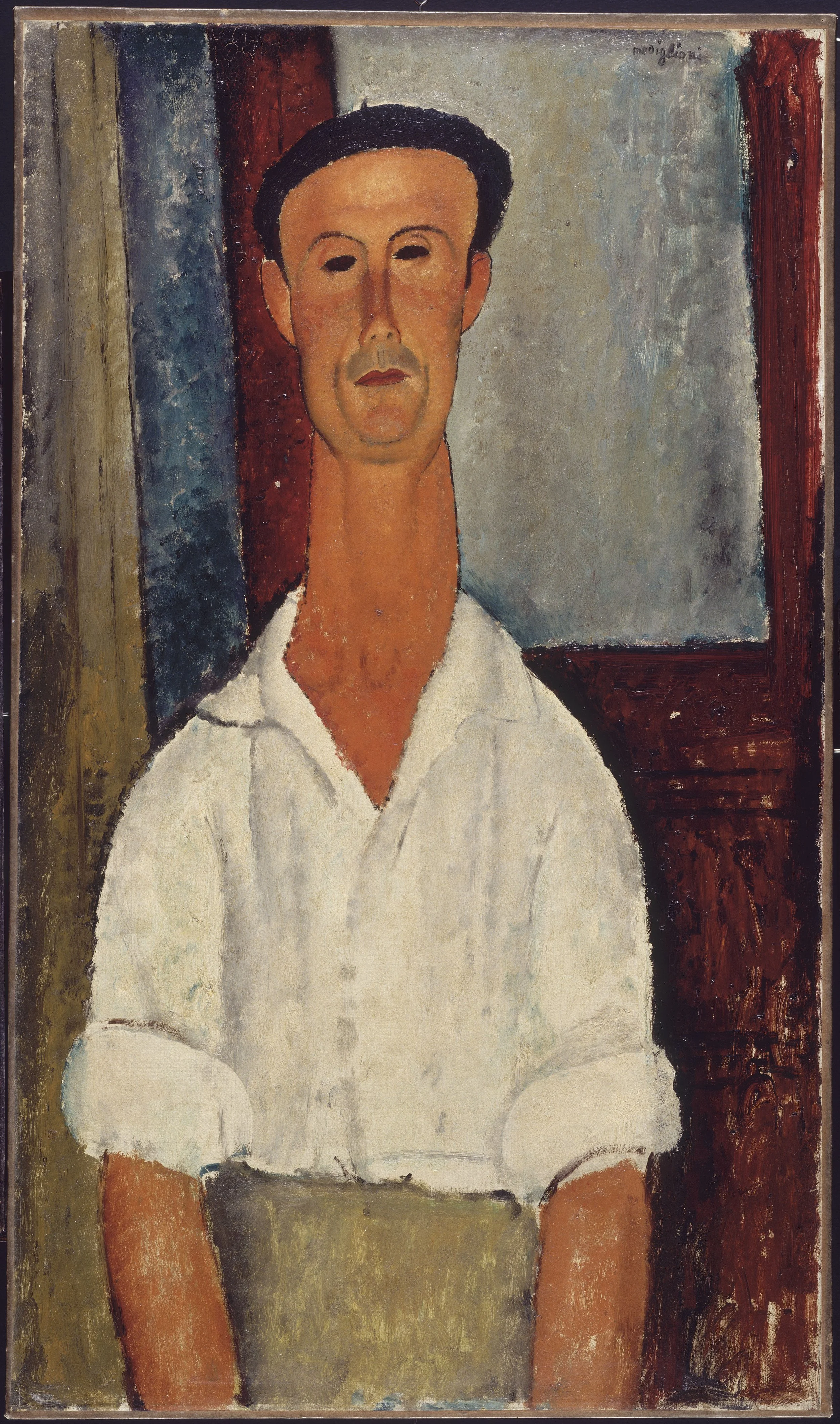

Gaston was shooting La Sultane de l’Amour at the nearby Villa Liserb studios in Cimiez, and Modigliani and Jeanne would often visit Gaston and Renée’s home in the afternoon to paint. Modigliani portrayed both of them and two paintings of Gaston are known today (fig. 4). Despite Renée’s later recollection of having posed for about “half a dozen” portraits and nudes, until now it was presumed that only Woman in a Yellow Dress (Renée Modot) had survived (fig. 3).[5]

(fig. 3)

Young Woman in a Yellow Dress (Renée Modot), 1918, Collezione Fondazione Francesco Federico Cerruti per l’Arte, on long term loan to the Castello di Rivoli Museo d’Arte Contemporanea, Turin

A persuasive clue in the identification of Renée as the model in Nude on a Divan can be found in the extensive research materials compiled by the art critic Alberto G. d’Atri during the 1950s, while preparing his ultimately unpublished catalogue raisonné of Modigliani’s work. D’Atri’s meticulous archives are housed at the Archives of American Art.[6] Among his photo archive is Nude on a Divan, indicating Chester Dale as the current owner, and identifying the model as “Mme. Gaston Modot”[7]; a photograph of Woman in a Yellow Dress names “Mme. Renée Montalant” as the model, referring to her by her maiden name.[8]The latter appears to be the correct reference, as both works were presumably painted in 1918, and records indicate that her marriage to Gaston took place in March 1919.[9]

(fig. 4)

Left: Gaston Modot, 1918, National Museum of Modern Art, Centre Pompidou, Paris. Right: Gaston Modot with Hat, 1918, (Gaston Modot au châpeau), oil on canvas, 45 x 27.3 cm, Simon and Marie Jaglom collection, on permanent loan to The Tel Aviv Museum of Art. Photo: Tel Aviv Museum of Art/Elad Sarig

In both Nude on a Divan and Young Woman in a Yellow Dress, Renée exudes a confidence that belies her age at the time these works were created. Then only twenty-four, she was Modigliani’s junior by ten years, but she appears entirely unintimidated in her poses, which are suggestive of the heroines in her husband’s films. Woman in a Yellow Dress bears an uncanny resemblance to Soledad, Gaston’s love interest in La Fête Espagnole, a celebrated avant-garde film shot in 1919 at the same Villa Liserb studios (fig. 5). Intriguingly, Young Woman in a Yellow Dress was once titled La Belle Espagnole.

(fig. 5)

Left: Ève Francis as Soledad in La Fête Espagnole (directed by Germaine Dulac in 1919 and released in 1920). Right: Woman in a Yellow Dress (Renée Modot), 1918.

Renée’s uninhibited and seductive pose in Nude on a Divan betrays a liberal and modern view of femininity, defying the contemporary notions of propriety. Her heavily applied eye makeup suggests that she was an early adopter of the look of the femme fatale, popularized in the 1910s by American silent film star Theda Bara (fig. 6).[10]

(fig. 6)

Left: Theda Bara in Cleopatra (directed by J. Gordon Edwards, 1917). Right: Nude on a Divan [detail], 1918.

Countless articles were published on Gaston during his prolific career that spanned over fifty years, but Renée remained largely hidden in the shadow of her immensely popular husband. A short interview she gave during the 1930s provides a rare but revealing glimpse into her appearance and self-assurance. Describing her as a “tall, brown-haired young woman with dreamy and intelligent eyes,” the journalist asked whether she was content being married to an actor, given the numerous female admirers that regularly surrounded him.[11] Renée confidently declared that, in her opinion, the excitement of the adventures in her husband’s professional life would enable him to resist “the charms of other women . . .”[12] Her only apparent frustration was “the missed projects, trips, vacations . . .,” abandoned at the last moment because of her husband’s unforeseen commitments.[13]

The strain evidently took a toll on the marriage as by the 1950s Renée was living with another man in Tourrettes-Sur-Loupe, a village with a vibrant artist community near Nice. In the relative obscurity of running a small housewares store, she gained some notoriety in 1958 when she mischievously posed next to a sculpture by Canadian artist Robert Roussil, which she had agreed to temporarily display in front of her store. La Famille, depicting a standing male nude with a crouching woman holding a child at his feet, caused a scandal among the more conservative community members, who decided to cover the man’s genitals with a loincloth. To her great delight, the photograph was published in the newspaper Le Figaro (fig. 7).[14] Renée carried the clipping with her as a badge of honor, and reveled in the fact that the photo credit had mistakenly referred to her as the author of the work. Roussil’s widow recalls Renée as an imposing and provocative figure, who continued to sport the short bob and heavy eye makeup from her younger years. Reminiscing with pride and some regret, she often spoke of her long-gone days as a Modigliani model. [15]

(fig. 7)

Renée Modot posing with La Famille, spruce wood, 1949, by Robert Roussil.

Le Figaro (January 25, 1958)

.

Renée once more gained attention in 1974 when a journalist with the International Herald Tribune interviewed her on the recommendation of a former Renoir model who had befriended her. Now 80 years old, she dwelled on her once-exotic appearance—which had inspired both Modigliani and Matisse to portray her—and coquettishly declared, “Je suis du siècle,” when asked about her age.[16] A little white lie, because she was born in 1894, Renée granted herself some creative license in crafting her own narrative. Jeffrey Robinson, her interviewer, recalls that Renée kept an image of Young Woman in a Yellow Dress, although she was unaware of its current location, nor did she remember specifically any of the other works for which she had posed.

In 1978, Renée passed away, an event that received no public notice. In a bittersweet twist of events, Young Woman in a Yellow Dress was concurrently on display in the sale preview of the Robert von Hirsh Collection at Sotheby’s, London, and was sold four days later—one of the sale’s star lots—exceeding its high estimate. Today it graces the walls of a palazzo, at the Castello di Rivoli in Turin, and the rediscovery of her starring role in Nude on a Divan now shines the spotlight on her at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C.

Leslie Koot

The Modigliani Initiative would like to thank the Castello di Rivoli Museo d’Arte Contemporanea, Turin and the Tel Aviv Museum of Art for providing us with the high-resolution images of the works published in this essay.

Special thanks to Danielle Moreau-Roussil, who generously agreed to a phone interview in which she shared her recollections of Renée Modot, whom she and her late husband, Robert Roussil, befriended in Tourrettes-Sur-Loup in 1958. I am also grateful to Jeffrey Robinson, who interviewed Renée in 1974 for the International Herald Tribune, and enriched this essay with his colorful anecdotes, told to me in a phone conversation (April 8, 2024). Renée’s quote in the image detail of Nude on a Divan which heads this essay is derived from his 1974 interview, comprehensibly cited in endnote 4.

Endnotes

Chester Dale papers, circa 1883–2003, bulk 1920–1970. Box 2, Folder 27: Collection Inventory #1, M, circa 1964. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. Link (accessed on November 1, 2023).

J.P. Crespelle, Montmartre Vivant (Paris, Hachette: 1964), 182.

Geneanet. Link (accessed on November 12, 2023) Genealogical records indicate that Gaston Modot divorced his first wife, Madeleine Georgette Flabeau, on December 3, 1917, suggesting that Gaston and Renée became a couple after this date.

Jeffrey Robinson, “Modeling for Modigliani,” International Herald Tribune (August 21, 1974): 14

Ibid.

Alberto G. d’Atri. Research material on Amedeo Modigliani, circa 1920–1962, bulk 1950–1959. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

Ibid. Series 7: Photographs, circa 1950s–1960s, Box 1, Folder 48.

Ibid. Folder 49.

Geneanet records indicate that the marriage of Gaston and Renée took place in Nice on March 15, 1919.

For a comprehensive discussion on the likely influence of female film stars on the use of heavy makeup by women in early twentieth-century France, see Nancy Ireson, “Modigliani’s Modern Women,” in Modigliani (London: Tate Publishing, 2017), 125.

Author’s translation of “Mme Gaston Modot est une grande et jeune femme brune aux yeux rêveurs et intelligents.” Jacqueline Lenoir, “Êtes-vous contente d’être marié à un artiste?...,” Paris-Films: tout le cinéma pour 25 centimes (April, 1931 ): 1.

Author’s translation of “il me semble que un artiste résiste mieux aux charmes des femmes…” Ibid.

Author’s translation of “Ce qui me désespère dans ma vie de femme d'artiste, ce sont les projets, les voyages, les vacances manqués…” Ibid.

Robinson (1974).

André Rousseaux, “L’homme rouge de Tourrettes,” Le Figaro (January 25, 1958): n.p.

Information kindly provided to the author by Danielle Moreau-Roussil in a phone interview (November 27, 2023).

The Modigliani Initiative