Gabrielle Soëne

Modigliani’s Elusive Model

Elle est très très belle…

– Blaise Cendrars[1]

Fig. 1

Portrait of a Woman (Mme C.D.), c. 1916.

Pola Museum of Art, Kanagawa, Japan.

Photo: Pola Museum of Art / DNPartcom

December 10, 2024

An elegant young woman with a distinctive hairstyle is recognizable in Modigliani’s oeuvre thanks to a half-dozen known pencil drawings and, presumably, one canvas that feature her likeness. (Figs. 1 and 2). Her hair is swept up into a bun and her face is framed by choppy bangs and longer side pieces. In the drawings, with characteristic economy of line Modigliani traces her delicate facial features and highlights the varied necklines of her fashionable attire. Two are helpfully inscribed with her name: “Gaby” and “Gaby Soene.” (Fig. 3 and Fig. 2, no. 3, respectively) With this latter detail we can identify Gabrielle Soëne (1888–1943) as the artist’s captivating model. Soëne was the daughter of a weaver and the eldest of eight children.[2] A skilled seamstress, she was an aspiring modiste who, by 1913, had resolutely moved to Paris from Tourcoing, in Northern France, a city close to the Belgian border.[3] She is but one of many aspiring female artists drawn to the French capital before the war.

Fig. 2

L to R, top to bottom:

1) Portrait de Gabrielle (page removed from a sketchbook, 43.3 x 26.4 cm; ex-collection Blaise Cendrars), Christie's, Paris, Arte Moderne, October 18, 2019, lot 212.

2) Portrait of Gabriele Souenne (page removed from a sketchbook, 42.4 x 25.7 cm; ex-collection Roger Fry). Statens Museum for Kunst, Cophenhagen (KKS1965-1).

3) Portrait of a Woman (graph paper, 26.7 x 21 cm). Sotheby's, Tel Aviv, 19th and 20th Century Paintings, Drawings and Sculpture, April 22, 1995, lot 99.

4) Portrait présumé de Gabrielle Soene (graph paper, 26 x 18 cm; ex-collection Blaise Cendrars). Beaussant Lefèvre & Associés, Hôtel Drouot, Paris, Art Nouveau, Art Deco, June 29, 2011, lot 113.

5)Tête de femme (25.5 x 20 cm). Audap Picard Solanet, Importants tableaux et sculptures des XIXe et XXe siècles, December 12, 1997, lot 132.

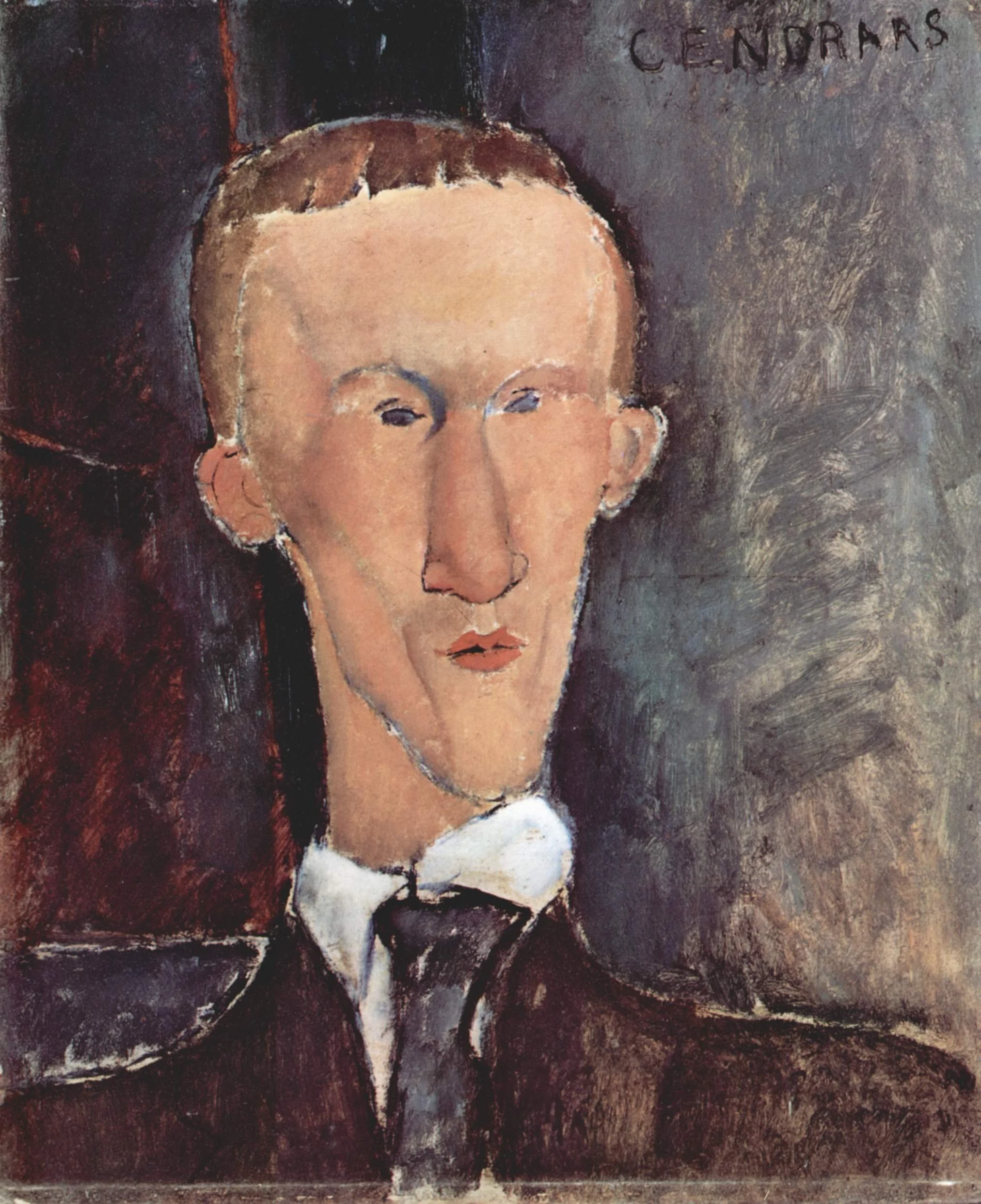

Gaby found work posing for artists, which is probably how she met Modigliani and, by 1914, she was considered his “good friend.”[4] In the summer of 1916, she became the lover of a member of his inner circle, the Swiss-born poet, Frédéric Louis Sauser (1887–1961), whose penname was Blaise Cendrars.[5] (Fig. 3) The couple holed up together at the Hôtel Notre-Dame in Paris and Gaby supported Blaise with her meager wages.[6] Financial challenges may have been one reason why their tryst was short-lived; the other would have been that Blaise’s wife, Féla, had recently given birth to their second child.[7] In early 1917, he reunited with his family in the South of France.

Fig. 3

Blaise Cendrars, 1916

Oil on cardboard (61 x 50 cm)

Private collection

At least three of Modigliani’s drawings of Gaby were made while she and Blaise were a couple.[8] In one, the bentwood chair behind her—a café staple—suggests that the three friends whiled away time together over coffee or drinks as the artist portrayed them in his sketchbook. (Fig. 2, no. 1) Modigliani inscribed the drawing “à Cendrars,” in large letters arranged vertically, possibly as a sentimental tribute to his friend who he knew was engaged in an ultimately impossible liaison.[9] Indeed, like a photograph capturing a happy moment in time, the drawing remained in Blaise’s possession for the rest of his life.[10]

In another example, Modigliani presents Gaby with the stature of a queen, seated in a throne-like chair with her head crowned by a headband. (Fig. 4) He makes a point of identifying her by adding her name in all capital letters, with a paraph added for emphasis. Presumably received as a gift from Modigliani, Gaby later inscribed the drawing herself and presented it to Cendrars (who she appears to have called “Freddy”), likely as a keepsake and parting gift.[11] In the lower right corner, her note reads: “To my dear friend F [illegible] from your only Gab. S. Friday 5 January 1917."[12] (Fig. 5) Cendrars’ biography confirms that in January 1917 he told Féla that his affair with Gaby was over.[13]

Fig. 4

Gaby. Portrait of Gabrielle Souenne, 1916, Graphite pencil on paper (page removed from a sketchbook, 43.3 × 25.6 cm)

Moderna Museet, Stockholm, Purchase 1970 (NMH 232/1970)

Fig. 5

(detail of Gaby’s inscription) Gaby. Portrait of Gabrielle Souenne, 1916,

Moderna Museet, Stockholm, Purchase 1970 (NMH 232/1970)

Though he left Paris at the start of the year, Blaise soon returned and he and Gaby reunited, if only briefly. That May, they attended the premiere of the Russian ballet Parade, which featured Picasso’s set designs.[14] In anticipation of this glamorous event, Gaby needed a suitable frock to wear so Blaise gave her his Modigliani portrait, suggesting that she take it to the designer Paul Poiret, a known modern art collector, to exchange for a dress.[15] (Fig. 3) Gaby returned with a crimson gown that she cherished and wore for years afterward.[16]

Soon after, Blaise and Gaby parted for good. He met the actress Raymone Duchâteau (1896–1986) in October 1917 and the two fell in love.[17] This may have inspired Gaby to leave Paris because she accepted the offer of Roger Fry (1866–1934), a painter and the founder of Omega Workshops in London, to become a dressmaker at this experimental venture.[18] In October 1918, Fry wrote to an associate to report that “The Omega goes a little better. We have found a marvelous modiste—a real genius—a little French lady who was starving in Paris.”[19] Late that same month, Omega presented an exhibition of the dresses of “Mlle Gabrielle.” (Fig. 6)

Sadly, any hope that Gaby might have had for accolades for her work would have been dashed when her creations received no press attention.[20] In addition, her prospects in London were grim, especially by the spring of 1919 when Omega Workshops was forced to close due to financial difficulties. Gaby’s small collection of Modigliani drawings probably helped sustain her life in London. It seems that she sold one to Fry, who reproduced it as Portrait of Mlle. G. to illustrate his essay, “Line as a Means of Expression in Modern Art,” in Burlington Magazine in February 1919.[21] (Fig. 2, no. 2)

Fig. 6

Roger Fry, Modern Paintings, Dresses and New Omega Pottery, 1918, Lithograph poster

V&A, London,

Given by Miss Margery Fry, J.P.,

sister of the Artist

(E.738-1955)

Gaby continued to model for artists and Roger Fry and Edward Wolfe (1897–1982) both painted her portrait around this time. (Fig. 7) Wearing what is believed to be one of her own dresses, she sat for them most likely in a room at Omega.[22] The two paintings are remarkably similar although Wolfe ultimately made the background of his portrait into a landscape.[23] Both works retained their original titles, identifying Gaby by her full name.

Fig. 7

Roger Eliot Fry (1866–1934)

Gabrielle Soëne, 1919. Oil on canvas. 50 × 30 in. (127 × 76.2 cm).

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of Mrs. Pamela Diamand, 1959 (59.132)

Image: Art Resource Inc.

“Gabrielle Soëne” became most widely known as the subject of a bronze bust by the celebrated British sculptor Jacob Epstein (1880–1959) and was also executed around the start of 1919. Epstein’s depiction skillfully conveys the smooth skin of her neck and shoulders, which are sheathed in a thin, silky wrap secured by a large brooch at front. His portrait of her attracted critical acclaim when it was exhibited at the Leicester Galleries in London in February 1920.[24] Displayed with other recent works by Epstein, the press singled out the bust of Gaby, calling it a “masterpiece of profound comprehension.”[25] A decade later, her name reached the United States when the Art Institute of Chicago and Toledo Museum of Art both acquired casts of Epstein’s sculpture in 1933 and 1937, respectively.[26]

When her name appears in literature, Gabrielle Soëne is referred to as a model for Modigliani, even though she is not currently associated with any of his paintings. In April 1931, a group exhibition at the Palais des Beaux-Arts, Brussels, included a small selection of Modigliani canvases, one of which is titled Portrait de Mme. B.C.[27] (Fig. 1) Could Paul Guillaume, who is known to have played a role in obtaining works for the show, have recognized her as the former companion of Blaise Cendrars and helped identify her portrait?[28] Though the painting received the same title in a second exhibition held several months later, thereafter the model became inexplicably known as “Madame C.D.,” which remains as the parenthetical identifier in the work’s present-day title.[29] Nonetheless, the painting bears a striking resemblance to Modigliani’s known drawings of Gaby. It is plausible that it was painted in the spring of 1917—at the time of the premiere of Parade—when she procured her red Paul Poiret dress.

For centuries, women have been portrayed in art; most remain nameless, their identities lost or never recorded. Gabrielle Soëne is an exception thanks to the artists who captured her likeness and thoughtfully preserved her name in their titles. Today, she can be identified as the model for artwork found in museum collections in Denmark, Israel, Scotland, South Africa, Sweden, and the US.[30] Though her own accomplishments are absent from the literature, her name and her youthful beauty endure. Identifying Gaby Soëne as Modigliani’s model, and making her story known, can perhaps begin to restore her place in history as both a popular muse and an artist in her own right.

Julia May Boddewyn

I am extremely grateful to Christelle Soëne, Gaby’s grandniece, who generously shared her research into her family. I am also deeply indebted to Matiur Rahman, editor of Prothom Alo, the largest circulated Bengali language daily in Bangladesh. His research into the life of Golam Ambia Khan Luhani (1892–1938)—Gaby’s husband as of late 1919—helpfully confirmed additional details about her life. From his archives, Rahman provided copies of Gaby’s letters written to her mother-in-law in 1924 and 1925, which allowed for the comparison of her handwriting to the inscription on the drawing in the Modern Museet, Stockholm. Matiur Rahman’s biography on Luhani, Ghulam Ambia Khan Luhani: The Narrative of an Unknown Revolutionary, was published in 2024 by Prothoma Prokashon, Bangladesh.

Endnotes

1. Miriam Cendrars, Blaise Cendrars (Paris: Éditions Balland, 1993), 325.

2. Emails to the author from Christelle Soëne (March 2024).

3. By 1913, she was romantically linked to Battiscombe “Jack” Gunn (1883–1950), an English Egyptologist living in Paris. This information comes from Albert T’Serstevens (1886–1974), the Belgian novelist who was Gunn’s friend. Letter from Albert T’Serstevens to Alain Rempfer, October 28, 1969. Digitized: http://alain.rempfer.free.fr/sitear/cendrars/t_serstevens_2.html (accessed Dec. 5, 2024)

4. Denise Hooker, Nina Hamnett, Queen of Bohemia (London: Constable, 1986), 120.

5. T’Serstevens claimed responsibility for introducing Blaise to Gaby. T’Serstevens letter (October 28, 1969).

6. Ibid; Jay Bochner, Blaise Cendrars: Discover and Re-Creation (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1978), 59.

7. Ibid.

8. Cendrars owned Fig. 2: nos. 1 and 4, and Fig. 3. Several drawings of Cendrars share the same dimensions and may have been made on the same day but none bear a corresponding inscription to Gaby.

9. The inscription includes extra letters in his name that are difficult to decipher; Modigliani’s inscriptions are often misspelled.

10. This drawing was sold at auction in 2013 by a descendant of Cendrars’s, as Portrait de Gabrielle. (see caption for Fig, 2, no. 1 for details.)

11. According to his daughter’s biography, some of Blaise Cendrar’s friends called him Freddy, short for Frédéric. Miriam Cendrars (1993).

12. “à mon très cher aimé F […] de sa seule Gab. S Vendredi 5 Janvier 1917." For more on this, see acknowledgement above.

13. Miriam Cendrars, Blaise Cendrars (Paris: Éditions Balland, 1984), 305.

14. John Richardson, A Life of Picasso: The Triumphant Years, 1917–1932 (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2007), 38.

15. Leonard Lyons, “The Lyons Den,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat (March 24, 1954): sec. B, p. 1. Lyons’ syndicated column appeared in a number of newspapers at the time that the Cendrars portrait was shown in New York in 1954. Since he was still alive at the time, it seems that Cendrars was the source.

16. “Gabrielle Soene, a Belgian who had posed for Modigliani, liked to wear a crimson dress which Poiret had made her in exchange for a Modigliani painting.” Richard Buckle, Jacob Epstein: Sculptor (Cleveland and New York: The World Publishing Company, 1963), no. 156, n.p.

17. The couple married in 1949 and were together for the rest of their lives.

18. Nina Hamnett is responsible for recommending Gaby to Fry. Hooker (1986), 120.

19. Letter from Fry to Rose Vildrac, October 1918. Denys Sutton, ed., Letters of Roger Fry, vol. I (New York: Random House, 1972), 355.

20. Judith Collins, The Omega Workshops (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1984), 161–2.

21. Roger Fry, “Line as a Means of Expression in Modern Art, Burlington Magazine 34 (February 1919): 66. Interesting to note is the fact that Fry kept his Modigliani drawing and his own painting of Gaby for his entire life. The drawing was sold as part of his estate and the painting was a gift to the Metropolitan Museum of Art by his daughter.

22. Collins (1984), 160.

23. The painting was sold as Portrait of Gabrielle Soëne. Sotheby’s, London, Modern British and Irish Paintings, Drawings and Sculpture, May 10, 1989, lot 73. It is now in the collection of the Tatham Art Gallery, Pietermaritzburg, South Africa.

24. The exhibition catalogue misspells her name as Gabrielle Saonne. Leicester Galleries, London, Recent Sculpture by Jacob Epstein, February 1920. Digitized by the Paul Mellon Centre, Yale University: https://www.paul-mellon-centre.ac.uk/archives-and-library/sculpture/epstein (accessed Oct. 15, 2024)

25. Yvor Byrne, “Epstein,” The New Witness 15, 380 (February 20, 1920): 248. Her name is spelled correctly here. Digitized: https://www.google.com/books/edition/The_New_Witness/qblOAQAAMAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&dq=%22Gabrielle+Soene%22&pg=PA248&printsec=frontcover (accessed Oct. 15, 2024)

26. After receiving a gift of a different Epstein bronze, the Toledo Museum of Art exchanged the work with the artist for a bronze cast of Mlle. Gabrielle Soene. The museum explained: “we consider [this] a more characteristic and typical work of the artist.” The Toledo Museum of Art News 81 (March 1938): n.p. Digitized: https://www.google.com/books/edition/Museum_News/pHDrAAAAMAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&dq=toledo+o+epstein+gabrielle+Soene&pg=PP520&printsec=frontcover (accessed Oct. 15, 2024) The plaster version of Epstein’s bust was reproduced in 1920 as Mlle. Gabrielle Soene. Bernard van Dieren, Epstein (London: John Lane, the Bodley Head and John Lane Company, New York, 1920), pl. XXX, illus. in b/w, n.p. Digitized: https://www.google.com/books/edition/Epstein/TFLqAAAAMAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&bsq=%22Gabrielle%22 (accessed Oct. 15, 2024) John Cournos, “Jacob Epstein: Artist-Philosopher,” The Studio 79, 328 (July 15, 1920): 178, illus. in b/w., p. 177. The Art Institute of Chicago no longer owns the Epstein bust. Likely at the same time that Gaby sat for Epstein, the English sculptor Eric Schilsky (1898–1974) produced a strikingly similar bronze bust of her.

27. L'Art vivant en Europe ran from April 25 to May 24, 1931, and included seven Modiglianis. An installation photograph confirms that this painting was shown and can only be Portrait of Mme. B.C. based on information provided in the exhibition catalogue. The painting then traveled to the Städelsches Kunstinstitut, in Frankfurt am Main, Germany, where it was included in Von Abbild zum Sinnbild (From the Image to the Symbol) from June to July 1931. It is listed as being in a private collection.

28. In the acknowledgements of the exhibition catalogue, the show’s main organizers, La Société “L’Art Vivant” and La Société Auxiliaire des Expositions, list the dealers who helped procure artwork from French and Belgian collections. L’Art Vivant en Europe exh. cat. (Brussels, 1931), 3.

29. The painting was shown again at the Palais des Beaux-Arts, Brussels, in November 1933, in a large monographic exhibition as Portrait de Madame C.D. It is also reproduced in the catalogue under this title. In his catalogue, Ceroni titles it Portrait de femme (Madame C.D.). Ambrogio Ceroni, Tout l'oeuvre peint de Modigliani (Paris: Flammarion, 1972), no. 117.

30. New York: Roger Fry, Gabrielle Soëne, Oil on canvas. The Metropolitan Museum of Art (59.132); Toledo, Ohio: Jacob Epstein, Mlle. Gabrielle Soene, bronze. Toledo Museum of Art (1937.2); Jerusalem: Jacob Epstein, Gabrielle Soene, plaster. Israel Museum (B66.1620); Edinburgh: Eric Schilsky, Gabrielle de Soane, bronze, National Galleries of Scotland (GMA 1525); Pietermaritzburg: Edward Wolfe, Portrait of Gabrielle Soene, oil on canvas, Tatham Art Gallery, South Africa; Stockholm: Gaby. Portrait of Gabrielle Souenne, Graphite pencil on paper, Moderna Museet, (NMH 232/1970); Copenhagen: Portrait of Gabriele Souenne, graphite pencil on paper, Statens Museum for Kunst (KKS1965-1).