“Première Exposition,” Lyre et Palette, November 19 – December 5, 1916

“These sexless beings . . . vermilion lips . . . and the eyes are not at the same level”

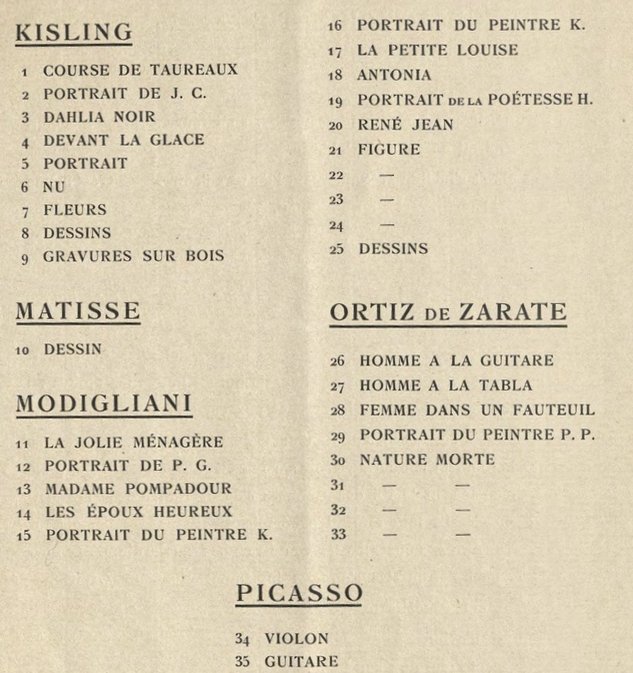

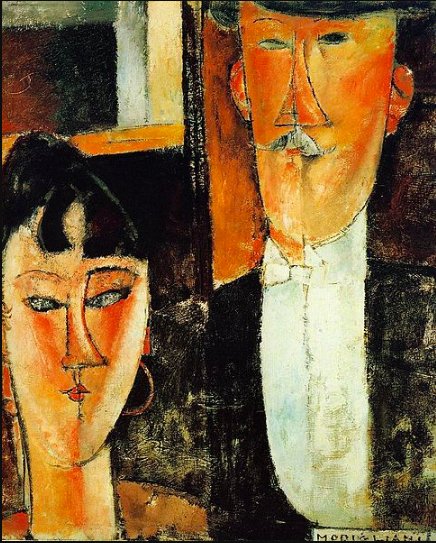

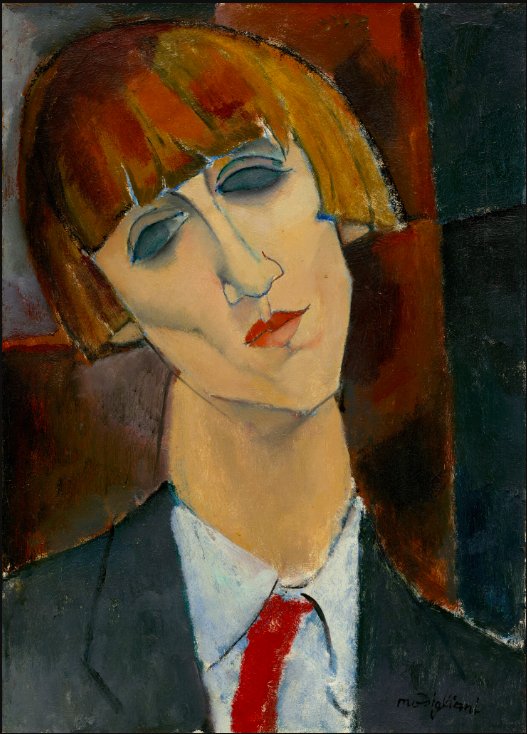

Madame Kisling, c. 1917. Chester Dale Collection, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

September 26, 2023

Modigliani in 1916:

At the Center of the Avant-garde

We enter. Three hundred people bump into each other confusedly. . . the very long hair of many men, the very short hair of many women, compose a first picture, and the most lively.

– Gaston Picard, La France (November 21, 1916)[1]

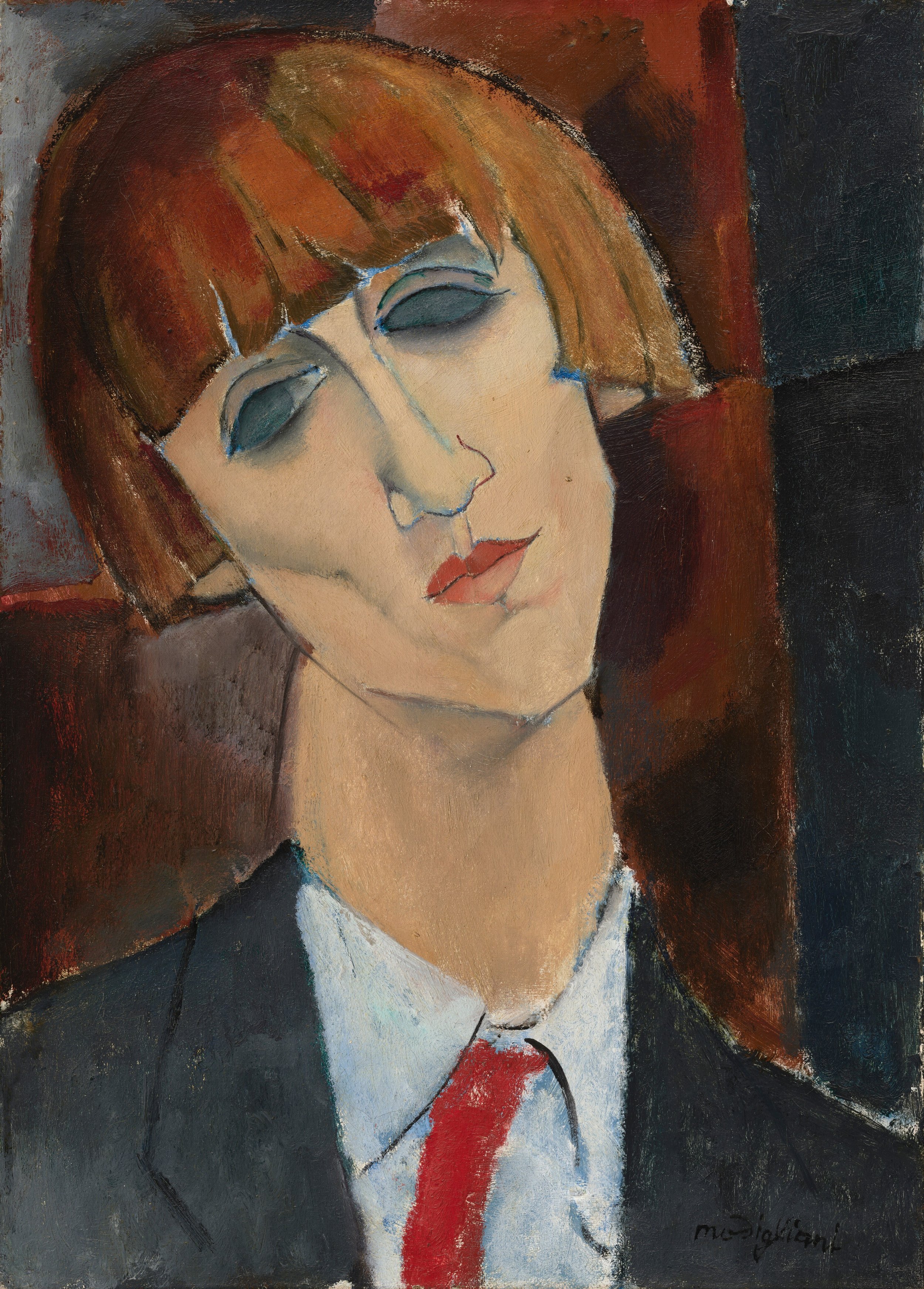

Against the backdrop of Erik Satie’s performance of a “musical moment,” notable literary and artistic personalities mingled with the picturesque crowd of Montparnasse artists and models before the bold canvases at the “Première Exposition” vernissage at Lyre et Palette. The group show featured work by such recognized artists as Henri Matisse and Pablo Picasso, as well as Manuel Ortiz de Zarate and Moïse Kisling. Modigliani, however, was by far the most prominently represented, with fourteen paintings and a group of drawings.[2] (Fig. 1)

(Fig. 1) Checklist, “Première Exposition,” Lyre et Palette, November 19–December 5, 1916

Most of Modigliani’s paintings on display were loaned by Paul Guillaume, the artist’s principal dealer, whose portrait by the artist was featured in the show. Guillaume complemented the exhibition with his private collection of African masks and sculptures; “Art Nègre,” the catalogue declared, “are exhibited for the first time not for their ethnic and archaeological qualities but for their artistic ones.”[3]

The animated opening, visually recorded by the Swedish artist Arvid Fougstedt, took place on November 19, 1916, and capped off a year of robust revival of artistic activity in Paris that emerged in the middle of the First World War. (Fig. 2) The Swiss painter Émile Lejeune began organizing concerts in his studio at 6, Rue Huygens, under the name “Societé Lyre et Palette.” De Zarate, the enterprising Chilean artist who had staged outdoor shows in Montparnasse during the summer of 1916, convinced Lejeune to add art exhibitions to his program. Kisling, a close friend and staunch supporter of Modigliani, assisted de Zarate in organizing the group show, and managed to effectively convert the event into a near-solo Modigliani exhibition.[4]

(Fig. 2) Arvid Fougstedt, At the exhibition (Lyre et Palette), 1916, Moderna Museet, Stockholm

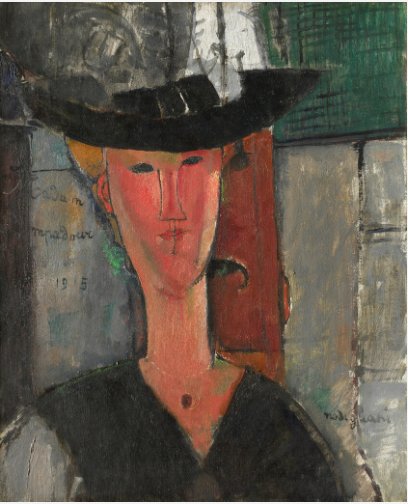

The show received extensive press coverage. La France’s Gaston Picard remarked, “It's new, bold, a bit awkward, always curious. These paintings . . . symbolize this kind of renewal of art, letters and music which began before the war and which the war did not kill.”[5] The art critic for the publication Paris singled out Modigliani’s portraits “which evoke the naively beautiful art of the Primitives . . . of remarkable shape and design, [the paintings] were a complete success.”[6] Writing for L’Évenement, Louis Vauxcelles reported, “I looked with great interest at the Modiglanis, a new style . . .”[7]

But the art on display drew the ire of others, who particularly expressed a distaste for its blatant androgyny, which they saw mirrored in the attendees. In Le Cri de Paris, under the title “Cubist Opening,” the columnist described the scene: “The audience of this show resembles the portraits, men-women, women-men. These sexless beings put on green or yellow makeup, vermilion lips . . . and the eyes are not at the same level.”[8] These comments appear to reference Modigliani’s canvases.

Some of Modigliani’s portraits that were shown can be credibly identified by their unique titles, while others have remained unclear. (Fig. 4) Number 20 poses a particular challenge: “René Jean,” suggests a male subject, and yet no one by that name is known to have been part of the artist’s circle. Lejeune’s later recollections reveal that the model was Renée Jean Gros, who would marry Kisling the following year.[9]

Interesting to consider is whether the male spelling of Renée’s name on the checklist was a typographical error or an intentional blurring of traditional gender norms. The latter conclusion is supported by Lejeune’s observation on how Gros perceived her name: “Renée Jean (two male first names she cared about).”[10]

Gros was an early adopter of the short bob haircut and routinely wore men’s clothing, such as ties and slacks. (Fig. 3) It seems that both her portrait as well as her presence at the vernissage may have triggered the critics’ derogatory remarks.

(Fig. 3) Moïse Kisling and Renée Gros-Kisling, undated photograph. (Image courtesy of Julie Martin)

Despite the positive reviews, Lyre et Palette was not a commercial success for Modigliani; reportedly none of his artwork sold.[11] Nonetheless, the show did solidify his reputation among the avant-garde and art dealers took note of his potential. Lejeune recalls that as a result of the show the art dealer and framer Constant Lepoutre entered into a short-lived agreement with the artist.[12] More significantly, the poet-turned-art dealer Léopold Zborowski began representing the artist, replacing Guillaume soon after the exhibition closed. In retrospect, 1916 turned out to be a pivotal year in Modigliani’s career. The prestigious shows he was included in that year garnered a level of attention that he never again saw during the remainder of his lifetime. [see Appendix]

Leslie Koot

Imagining an Illustrated Catalogue

(Fig. 4) Modigliani paintings exhibited at “Première Exposition,” Lyre et Palette

Left to right, top to bottom:

11) La Jolie ménagère, 1915, Barnes Collection, Philadelphia

13) Madam Pompadour, 1915, Art Institute of Chicago

14) Les époux heureux, 1915, Private collection

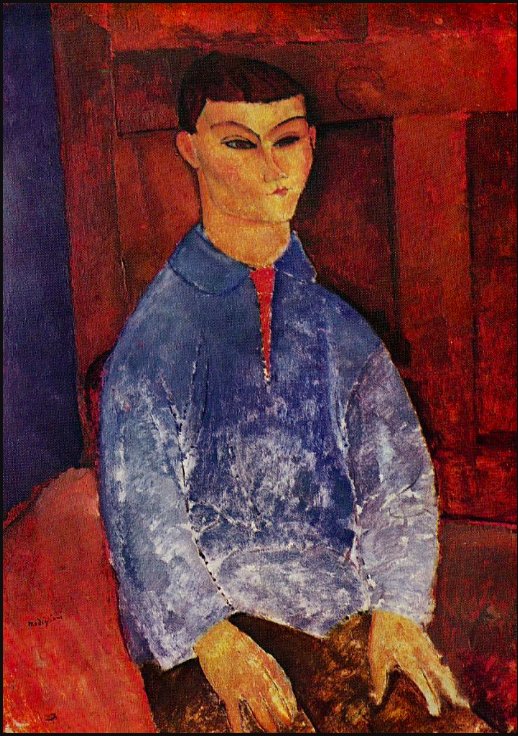

15 or 16) Likely Portrait du peintre K., 1916, Present whereabouts unknown[13]

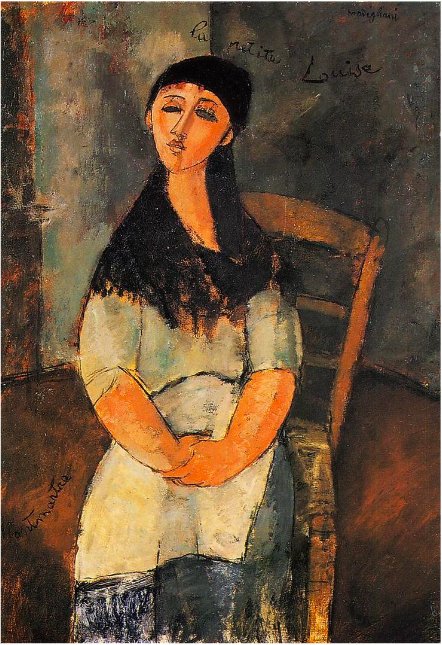

17) La petite Louise, c. 1915, Private collection

18) Antonia, c. 1915, Musée de l'Orangerie, Paris

20) Likely René Jean (Madame Kisling), c. 1917, Chester Dale Collection, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.[14]

NB: Not reproduced are 12) Portrait de P.G. and 19) Portrait de la poétesse H., of Paul Guillaume and Beatrice Hastings, respectively. There are four portraits of Guillaume that may have been displayed and an even greater number of Hastings.

Appendix

1916 Exhibitions Featuring Modigliani’s Work

Paris, March–April 1, 1916. Chez Madame Bongard, Exposition de dessins en blanc et noir.

New York, March 8–22, 1916. Modern Gallery, Works by Modernist Sculptors.

Zurich, June 1916. Cabaret Voltaire, L'Exposition Cabaret Voltaire.

Paris, July 16–31, 1916. Salon d’Antin, Galerie Barbazanges, L'Art Moderne en France.

Paris, November 19–December 5, 1916. Lyre et Palette, 1re exposition: Kisling, Matisse, Modigliani, Ortiz de Zarate, Picasso, Sculptures négres,

Endnotes

Author’s translation: “On entre. Trois cents personnes se heurtent confusement . . . les cheveux trés longs de beaucoup d’hommes, les cheveux très courts de beaucoup de femmes, composent un premier tableau, et le plus vivant.” Gaston Picard, La France (November 21, 1916): 2.

Emile Lejeune, “Montparnasse à l’Epoque Héroique: Un peintre genevois réunit dans son atelier les chefs de file de la nouvelle peinture,” Tribune de Genève (February 8, 1964), article no. 7. Lejeune recorded his later recollections of Lyre et Palette, and the exhibitions held there, including the “Première Exposition,” in a series of articles, which were published in the Tribune de Genève between January 25 and March 19, 1964. Special thanks to Robert Oliva for sharing transcripts of the articles.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Author’s translation: “C’est neuf, hardi, un peu gênant, toujours curieux. Ces peintures . . . symbolisent cet espèce de renouvellement de l’art, des lettres et de la musique qui commença avant la guerre et que la guerre ne tua pas.” Picard (November 21, 1916): 2.

Author’s translation: “Les portrait de Modigliani qui évoquent l’art naîvement beau des Primitifs . . . d’une forme et d’un dessin remarquables eurent un plein succès.” Paris (November 26, 1916): 3.

Author’s translation: “J'ai regardé avec intérêt les Modiglianis, nouvelle manière. . .” Louis Vauxcelles, “La Vie Artistique; quelques cubistes,” L’Évenement (November 21, 1916): 2.

Author’s translation: “Ces êtres sans sexe se fardent en vert ou en jaune, bouche vermillon . . . Et les yeux ne sont pas au même niveau.” “Vernissage Cubiste,” Le Cri de Paris (November 26, 1916): 9–10.

Lejeune. Renée Jean Gros and Moïse Kisling married on August 12, 1917, amid a celebration that lasted for three days. For a detailed account, see Billy Klüver and Julie Martin, “Love and Marriage,” Kiki’s Paris: Artists and Lovers 1900–1930 (New York: Abrams, 1989), 79.

Lejeune.

Ibid.

Ibid.

The exhibition included two paintings titled Portrait du peintre K., a reference to Moïse Kisling. The painting reproduced above belonged to Paul Guillaume by the spring of 1916 and was photographed in his apartment. Klüver and Martin 1989, 77. The second Kisling portrait was either Ceroni 98 (Pinacoteca di Brera, Milan) or Ceroni 154 (Lille Métropole Musée d'art moderne, d'art contemporain et d'art brut, Villeneuve-d'Ascq, France).

While there are two known Modigliani portraits of Renée Jean Gros, Madame Kisling is likely the one exhibited at Lyre et Palette: Madame Kisling, c. 1917, Chester Dale Collection, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. 1963.10.175. Link to website. The second portrait of her has “RENEE” inscribed on the front of the canvas. This would have been in obvious contradiction to the male variant printed in the checklist: Renée, 1917, Pola Museum of Art, Kanagawa, Japan. Link to website.

Assuming that Madame Kisling was the painting exhibited in 1916, Renée Jean Gros would not yet have been Madame Kisling; her marriage to Moïse Kisling took place nine months later. (see fn. 9) The correct dating of the portrait would be 1916. The collection inventory card for this work acknowledges: “Painted in 1917 or possibly slightly earlier.” Chester Dale papers, circa 1883–2003, bulk 1920–1970. Box 2, Folder 27: Collection Inventory #1, M, circa 1964. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

The Modigliani Initiative